Before heading out to meet my friend near London Bridge Saturday night, I stopped to change my socks. As a result of this 2-minute task, I narrowly missed my train and arrived in central London 13 minutes later than I’d meant. That decision to change my socks may have saved my life.

At 21:18 Saturday night, I boarded a train from Kew Bridge to central London. Forty-eight minutes later I was leaving London Bridge station and walking towards Borough Market, where on a normal Saturday afternoon you’ll find dozens of vendors selling cheese, brownies, and street food from all corners of the globe, and on a normal Saturday night you’ll find thousands of people enjoying pints and bites in dozens of pubs and restaurants.

A man near the tube exit was loudly calling out a name and searching frantically—I assumed he’d lost his child. Poor guy, I thought. I hope he finds his kid.

As the man searched to and fro, one or two dozen people suddenly rounded the corner, running, in groups of two and three. They were shouting, but it wasn’t obvious whether in fear or revelry; I assumed they were just drunk, maybe on a stag party. Or maybe they were filming a segment of The Amazing Race. Thinking nothing of it, I continued around the corner from which the running people had just come.

That’s when I saw the bodies. Three people curled on the Borough High Street sidewalk across from me, spaced maybe 30 meters apart. A bicycle lay on its side next to one of them, and a bicycle wheel was crunched against the curb next to another. A figure squatted next to one of the people, clutching her hand and pleading desperately with her to stay with him. First responders and police were already on the scene, with sirens and flashing lights announcing the arrival of more.

Had there been an accident? Perhaps a car had hit some cyclers and knocked them to the curb… but then, where was the car? Or perhaps two cyclists had crashed into each other? But no, they were too far apart. What was going on? My mind struggled to make sense of these scenes that didn’t quite fit together. Cautiously, I approached one of the people on the ground.

Blood stained her torso, and she was not moving. A man in uniform approached me. “What are you doing? Get out of here!” he ordered.

What the hell is happening?

Not knowing which direction was safer, I resolved to make it to where my friends were, following Google Maps on a shortcut through the deserted market. I stepped out of the market into a side street.

I knew I was in the middle of a terrorist attack when I saw the fourth body. A woman lay crumpled on the ground in a pool of blood just next to my feet. On a totally different street: too far from the other bodies to have been an accident. There was only one explanation for what I was seeing.

Fear welled up inside of me. Not a fear I’d ever experienced before: this was the fear of death. The knowledge that at any moment, a bomb could rip through the buildings around me, or a man could round a corner spraying bullets from a machine gun.

This couldn’t be real. But then, it had happened before to other people—in Paris, in London a month ago, and in Manchester just the week before—so why shouldn’t it happen to me? Police were running everywhere. Sirens were screaming a block away. This was real: at any minute I might become the proverbial “someone else”.

I stumbled a few more dazed steps forward before realizing I needed to get inside, and fast. No time to find my friends. I ducked into the nearest restaurant, a chocolate bar called Rabot 1745. Inside, people were still chatting, out on dates and clearly too into their partners to yet be aware of the death and mayhem going on just meters away.

At that moment the doors crashed open and a woman stumbled in. Blood was all over her hands. Seconds later a collective shriek arose outside and a frenzied commotion, as animals stirred from grazing by a predator’s charge, became a stream of panicked people pushing their way in behind her, clearly fleeing the attackers. A waitress positioned herself by the entrance and, once the last person was through, slammed decisively shut the doors and locked them. Only a thin sheet of glass stood between us and whatever was outside.

Next decision: up or down, basement or rooftop? I considered my options. In the basement I could lock myself in the bathroom, but then I’d be trapped if the attackers forced their way in. On the rooftop deck I would have the higher ground, and could jump down to the market below if necessary—assuming there were not more attackers or bombs down there.

Rooftop it was.

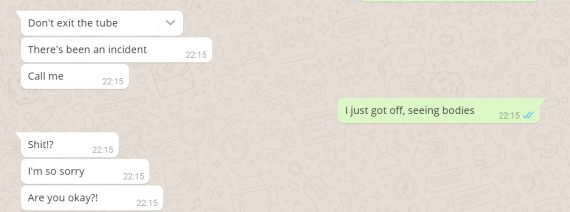

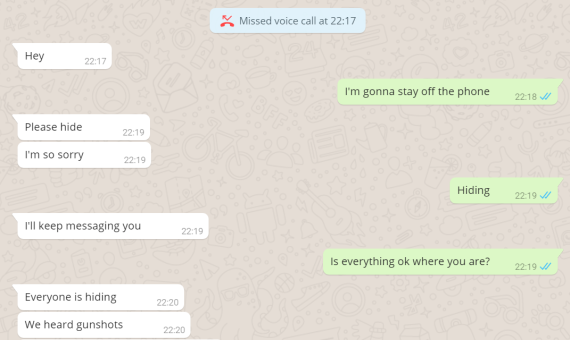

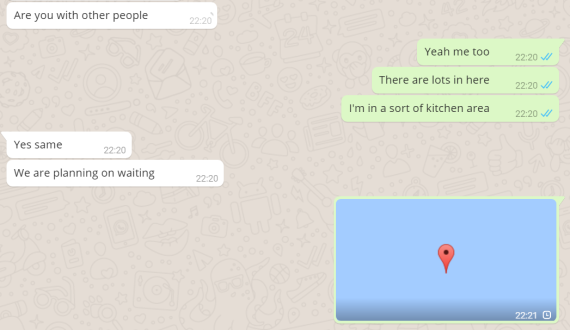

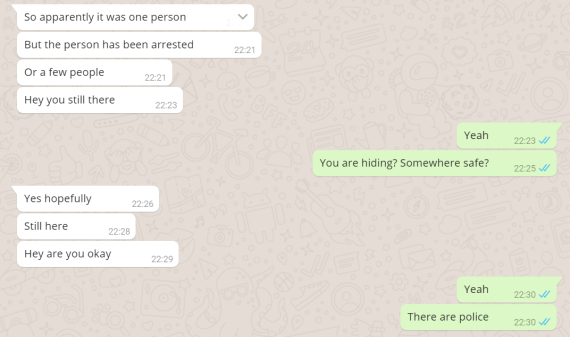

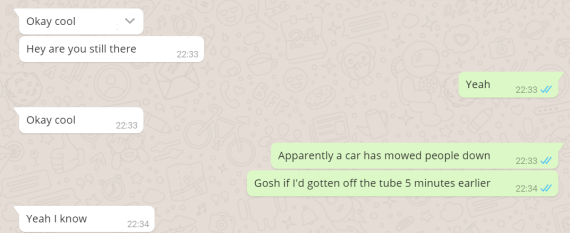

Racing up the stairs I felt my phone buzz. I checked Whatsapp. There was a message from my friend.

I called back and had just started to explain the situation when I stepped out onto the roof deck.

TAT-TAT-TAT-TAT-TAT-TAT-TAT-TAT

Machine gun fire or an explosion rang out from the market below.

“SHIT! SHIT!”

I hung up and fled back indoors with the others from the roof deck. Unsure of whether we were hearing guns or bombs or even who was firing them, I instinctively looked for the most solid place in the building, farthest from the external walls; my childhood growing up in tornado alley turned out to be good preparation. I crouched behind the bar.

A waitress shut off the lights—better that it looked like the place was closed. And we settled in, listening.

“Do you have any sharp knives?” I asked another waitress.

“Nope, all we’ve got are these ridiculous butter knives.”

That wouldn’t do. But I did spot a rack of plates and some espresso cups. A long shot, but if anyone came up the stairs and around the corner, throwing cups and smashing plates on a face might buy enough time to get away.

My heart pounded. So this was the meaning of terror: being trapped in a restaurant with glass doors, and only a few dinner plates and espresso cups between you and the bad guys, not sure if you should fight or flee. The feeling was beyond just fear: it was the feeling of being hunted. Fear had intent. And it had a face. We just didn’t know what the face looked like yet.

My phone had been ringing. I took it out.

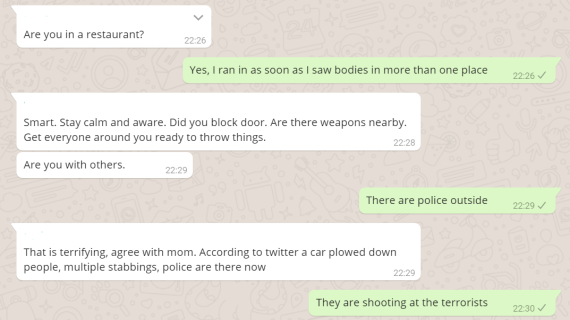

I messaged my family and coworkers, then got on Twitter to try to figure out what the hell was going on. We were all hearing rumors, but no one knew the truth. I was getting messages all the time.

Every time the pipe near the sink bubbled, my heart leapt into my throat. We still didn’t know if there were terrorists still on the loose, or if a bomb might go off any minute, or if the glass doors to the restaurant would shatter and gunshots start ringing out again. After surviving 5 years of boda bodas in Uganda, was I going to finally get killed by terrorists? I got a message from my family (names blocked out for privacy).

And then I saw them. Not attackers, but blue lights now flashing outside—I could see their glow illuminated on the darkened ceiling. Dogs were barking as well.

The police had won.

I can’t tell you the visceral gratitude I felt toward the police at that moment. It was a “the Eagles are coming!” moment—rescue from Mount Doom arriving on the horizon—only this wasn’t a fantasy book. These were real men and women outside—not in the shelter of a restaurant but in the thick of chaos—putting their bodies between us and whatever was out there. No one knew if more attacks were coming, but if they did, it would be them, not us, who took the first brunt of any new attack. Because it was their job to do so.

The London Metropolitan Police were heroes that night.

I later found out that the gunshots I’d heard at 22:16 on the rooftop were from police machine guns shooting dead all three terrorists in the street below. The attack started at 21:58, the police were called at 22:08, and the terrorists were dead by 22:16.

8 minutes.

That 8-minute response time saved who knows how many lives that night; if the terrorists had continued for 15, 20, 30 minutes, many more would have died. Maybe they would have even smashed through the doors of Rabot 1745 and slaughtered all of us who were sheltered there.

The men and women of the Metropolitan Police saved my life and many others Saturday night, and I am forever grateful to them, and to police officers worldwide, who risk their own lives to protect the rest of us. I was praying to God in that dark corner, but it was the police I’d been praying He’d send.

The Rabot 1745 staff were no less brave. In the face of horror, and with no special training, they did not panic, but had the calmness and presence of mind to lock the doors, keep everyone calm inside, and turn out the lights. Bouncers at other bars saved lives by fighting off the terrorists with tables and chairs, but I have no doubt that the actions of the staff at Rabot saved lives as well by denying the terrorists access to the people inside. I want to thank them as well.

We heard shouting from downstairs—the police had made their way into the building and were ushering people out. “Police! Police! Everything is okay!” We ran down the stairs under the watchful eyes of armed police in full body armor and face shields, machine guns drawn and ready. “MOVE, MOVE, MOVE!” they commanded. Ahead was a tunnel of similarly armed officers protecting our retreat.

As we ran down the stairs I heard one of the waitresses announce, “needless to say, no one needs to pay for their bill tonight.”

“Dammit!” one of the patrons called back cheekily. “I just paid 15 minutes ago!”

***

At least 7 people were savagely murdered that night, and 48 more injured. I was lucky to escape. My friends were evacuated as well. We celebrated survival the next day with that most English of traditions: a Sunday roast.

My mom later told me “I never thought I would get text messages like that.”

I never thought I’d have to send them.

But now that I have, and things have calmed down a bit, I’ve had some time to write down some thoughts on the experience of terrorism and what comes next. Three come to mind.

1. Evil is evil

Many of us, especially on the political left, have a tendency to try to find moral equivalency between acts for which there can be no equivalence. Self-criticism is of course one of the most important practices to follow in a world that’s rarely black and white, and we of course need to try to understand the causes of atrocities in order to stop more from happening. But it’s important not to conflate unintended consequences of well-meaning actions with willful acts of intentional murder, and we must avoid sliding down the slippery slope from useful understanding to moral justification.

I’ve seen the bodies. Other people saw the stabbings. Seven lost their lives. At some point it doesn’t really matter how alienated someone is, or how bad the injustices are they think they are fighting against. Someone who can find it within themselves to stab men and women in the neck who can’t fight back has made themselves evil.

It’s black and white.

2. Give

Adam Smith once wrote that a man would care more about “the most frivolous disaster which could befall himself” than the most horrible disaster wiping out a whole country:

If he was to lose his little finger to-morrow, he would not sleep to-night; but, provided he never saw them, he will snore with the most profound security over the ruin of a hundred millions of his brethren, and the destruction of that immense multitude seems plainly an object less interesting to him, than this paltry misfortune of his own. To prevent, therefore, this paltry misfortune to himself, would a man of humanity be willing to sacrifice the lives of a hundred millions of his brethren, provided he had never seen them? (The Theory of Moral Sentiments)

Westerners share a certain common heritage, so we naturally sympathize with Londoners more than with victims from different cultures – say, Africa or Asia. But even as sympathy pours out for London, there were no Facebook check-ins or flag overlays when 150 were killed in Afghanistan just 3 days earlier. 20 million people are at risk of starving in South Sudan, Nigeria, Somalia, and Yemen. And their ordeal can’t be ended in 8 minutes by police; they endure it day after day, and may for the rest of their lives.

If you are seized by the impulse to donate to the victims of terror in the UK, do it. Then match those gifts with donations to organizations working in some of the harshest parts of the world. Some good ones working in South Sudan are Mercy Corps and MSF (Doctors Without Borders).

3. Keep calm and carry on

I wish we hadn’t built a memorial after 9/11. I wish we’d just rebuilt those same two towers, but even taller, if only to say “You didn’t beat us: we still here. You knock down these towers, we build them right back.”

The West is still strong, and no one can defeat it from the outside. That’s why terrorism exists as a tactic: terrorists know they can’t beat a Western army on the battlefield, so they resort instead to cowardly and cruel acts of killing civilians to try to provoke us into beating ourselves. They want us to overreact and do something that accidentally kills civilians in Muslim countries or alienates Muslims in Western countries. That’s how you recruit people to your side: by showing people they’re the “us” in a war of us-against-them.

And as scary as Saturday’s events were, I continually remind myself that statistically speaking, the most dangerous thing I did Saturday was the taxi ride from the airport. Indeed, terrorism is one of the least likely ways for you to die—about four times less likely than from a heat wave, and only slightly more likely than “asteroid (global impact)” (although that’s little comfort to the victims). Meanwhile we ignore other forms of violence. The same night there was another stabbing in London, but it was declared “unrelated” and dismissed. Two days later a factory worker in Florida shot and killed 5 former colleagues, but you don’t hear politicians criticizing the mayor of Orlando; after all, the shooter was white, so the killing was “only” a murder, not terrorism. Can you see the difference? Neither can I.

And really, how much more can we do to prevent terrorism beyond what we’re already doing? The Metropolitan Police responded on Saturday in 8 minutes! Maybe they could have cut it to 6 or 5, but it’s difficult to see how much better they could do, or how many more lives it would have saved. Donald Trump wants a wall and a travel ban, but many terrorists these days are born in the very countries they attack, radicalized online; walls may keep the terrorists in, but they can’t keep the internet out.

It’s only if we give in to fear that the terrorists win. If we step up the crackdowns on Muslim communities, how many more young men will be turned to terror versus how many will be caught before an attack? If we keep giving up ever more of our freedoms in exchange for ever smaller reductions in the already low risk of terror, how long before it will end? Do we want to have checkpoints on every corner and metal detectors in every restaurant, movie theater, and shopping mall? Or to have the government arresting people for things they say on TV?

This is not to say that we shouldn’t have common sense security measures to minimize attacks, and punish or kill those who commit terror. Of course we should do both.

But we don’t control as much as we think we can: at some point bad things just happen. If all a terrorist needs is a van and a couple of big knives, there will always be some chance of ending up in a situation like I was in. And we have to carry on.

If we give into fear, we will lose more of the freedoms that we seek to protect, and create more of the enemies we seek to defeat. But if we can live our lives confidently and with open eyes, if we can welcome people from all faiths and all parts of the world, if we show our values by example instead of forcing them on others—“being good in order to be great”—I believe horrors like Saturday’s can be made as rare as possible.

In other words, we should be like this guy, who fled the terrorist attack—but not without grabbing his pint first.

I’ll certainly be back at London Bridge for a pint. Hope to see you there.

Posted by Nick Kennedy on June 6, 2017 at 4:18 pm

Wow this is really good. Man so scary glad you are ok

>

Posted by Andrew on June 6, 2017 at 4:22 pm

Believe me, I am too!

Posted by Harriett E. Kelley on June 6, 2017 at 4:34 pm

Thank heavens for those socks. So scary.

Posted by wifiwidow on June 6, 2017 at 10:21 pm

Incredible story, glad I stumbled across this post.

Posted by becswan on June 7, 2017 at 7:47 pm

Great read Andrew; you put into words a lot of the thoughts I’ve been having following these attacks. Thankful you were able to stay safe.

Posted by J on June 7, 2017 at 10:22 pm

I was actually interested until I got to the part where it said after surviving 5 years in Africa!!! Was that really necessary, you need to be specific what country!!! I’m Kenyan and I hate it when people paint a horrible picture of Africa like there’s no civilisation!! Smh

Posted by Andrew on June 10, 2017 at 12:50 pm

Apparently 5 years in Africa isn’t enough to have taught me not to put my foot in my mouth! Thanks for pointing this out. To be fair, given the number of bus and motorcycle rides I’ve done in Uganda and Kenya, I am (statistically speaking) a lot more likely to be killed in an auto accident in either of those countries than in the UK (837 traffic fatalities per 100k motor vehicles per year in Uganda and 641 in Kenya, vs. 5 in the UK).

But the generalization “Europe = safe, Africa = unsafe” is of course unproductive and paints a misguided picture (and doesn’t help me either given that I want more investment to come to East Africa, and more people to come see what an underappreciated place it is). The specific irony I’d meant to get across is, given how frequently I complain about how much more people worry about security than things that are actually more likely to kill them (like traffic accidents), was I actually going to become a victim of a statistical improbability?

I’ve updated the post to hopefully make this clear.

Posted by davidadeyalo on June 9, 2017 at 7:21 am

Andrew, you don’t remember me but we met years ago at your apartment in DC. Your old roomate shared this story with me. It’s a powerful story and I appreciate you sharing. I encourage you to really seek to understand everything that you saw. Thank you for telling us your story, and I hope that it helps others stand up in the face of fear. Fear is rational. How we face our fears, as you did, is important.

Posted by Andrew on June 10, 2017 at 1:12 pm

I remember that! Thanks for checking – I’ve been telling people that statistics and beer are the best way to get over terrorism

Posted by Rajashree on June 14, 2017 at 3:10 am

LOVED that! ‘I’ve been telling people that statistics and beer are the best way to get over terrorism.”

Posted by Jerry on June 10, 2017 at 3:26 am

Andrew

First off glad to hear you made through something so tragic. You have a gift for articulating events and appreciate the fact that you have done so. Stay safe and continue to live full.

Posted by Dave on June 11, 2017 at 8:11 am

Well said my friend. I’ve never been caught up in the mayhem but if I am I hope I can respond as you do here.

Posted by finktart on June 13, 2017 at 9:01 am

This was a very good read. When the attack happened, I wondered if I shouldn’t revisit London again because compared to the West, here in South East Asia, we’ve been blessed to not have that sort of experience yet; our countries’ securities are taking measures though. Your post has changed my mind. I hope to visit London again someday. Thank you for being so forward-thinking and positive. 🙂

Posted by Andrew on June 15, 2017 at 5:37 am

Good! And given that the UK has one of the lowest traffic fatality rates in the world, you’ll be just as safe overall as anywhere. Glad to have helped.

Out of curiosity where had you seen this link? Lots of people in Singapore and SE Asia are reading, but not sure what is causing it to spread there!

Posted by Nastasha K. on December 16, 2017 at 8:08 pm

My apologies for a very late reply. >.< The link was shared by an acquaintance on Facebook. I'm not exactly sure how links get shared there but it could be due to the fact that many Singaporeans travel out of the country often so we always share news about worldwide events.

Posted by Human on June 13, 2017 at 10:34 am

Now, imagine how the terrorist acts done by US,UK and Israel that has created/fabricated and instilling war in Palestine, Iraq, Syria, Yemen, Libya and Afghanistan.

Bombs, Missiles, Machine guns, carpet bombing, phosphorus bombing, artillery strikes, snipe shots and many more atrocious act by US, UK, Israel and all the terrorist organisation that they have produce impact on the civilians of that countries.

What you have experience is less than 30min of your life. The civilians in the countroes I mentioned have experience since 70 years ago till present.

PS. Thank god you are alive. Those who are injured, god bless them with speedy recovery and those who have moved on, god bless them and may rest in peace.

Posted by jessica on June 13, 2017 at 12:43 pm

thanks for the good read. a little reminder that we should always give. god bless

Posted by rbaldwin5 on June 13, 2017 at 5:39 pm

Wow, I got chills reading this. So true and so well said.

Posted by I’M FEATURED IN JUNE’17 ISSUE OF CLEO MAGAZINE! – Flying Pistachios on June 14, 2017 at 1:07 pm

[…] ending this post, I would like to urge everyone to just take another 10 minutes to hop over to Afrikent’s words space – he was in the recent London Bridge terrorist attack and witnessed the horrific event. Writing reviews and sharing my daily life in words are a […]

Posted by My Ancestors Fought for the Confederacy. That Doesn’t Mean I’m Proud of that “Heritage” | Afrikent on August 17, 2017 at 2:12 pm

[…] « I was in the London Bridge terrorist attack: it showed me why we are right not to be alarmed […]